The Modality of Young People’s Discourse

The given paper analyses the modality of teenage girls' and boys' conversation on the basis of the Georgian lingual material. The corpus of the paper is presented with the transcriptions of audio/video recordings of the discourse of the youth (12-18 years old) from Kutaisi (Saghoria District). The transcriptions were made by using GAT (Conversation Analytic Transcription System - Gesprächsanalytische transkription[1] ). The paper presents and discusses 5 dialogues.

The modality of conversation is important for the ethnography of communication. Interactive modality is a method, which gives symbolic meaning to lingual expressions, lingual actions and particular situations. It can be serious, pathetic, aggressive, having a playing or a joking character, etc. Interactive modality is stipulated by interactants. It has the greatest influence on the act of speaking and shows a speaker's perspective. The change of modality depends on the speaker and his/her partner. The latter either supports the changes or rejects them. Therefore, the modality is developed or stopped. It's necessary to know the partner's communicative competences for a "smooth" development of the interactive modality. It can comprise the whole conversation, its parts or separate lingual expressions, for instance, a serious conversation can be stopped by short joking inclusions.

Young people tend to entertain and joke. 90% of their conversation contains joking and irony [Beirbach, 1996: 262]. It's difficult to draw a border between a reality and a fiction, between imaginary stories and real ones enriched with a fictitious material. There are many cases, when young people compete in making the stories as absurd as possible. Something that is abusing and unacceptable for adults, can be a mark of intimacy and benevolence for the young people.

The most widespread modality of young people's discourse is humor - a mixture of jokes and unserious talks. Humor is the phenomenon of a group. Every company has a specific manner of telling a joke. A frivolous modality of entertainment in young people's groups has the function of solidarity and mutual understanding. By means of the humor they express their positive and negative attitudes towards someone or something. The humor of boys is vulgar. Hence, girls are also familiar with the jokes of the given modality.

Humorous stories and telling jokes are important characteristics of young people's discourse. Girls often tell humorous stories, while boys prefer jokes.

Example 1. Girls are speaking:

- B. Oh, do you know?

- That I have deceived Chumburidze?

- C: No

- A: Oh, it was great

- B. Shortly (-)

- I entered from my friend's site

- Excuse me

- E Where have you bought these red boots?

- A. Wearing red boots on the main

- C. Wow, yes, red ((laughs))

- A: and writes to me at the same time

- G: Girl, somebody asks me where I bought the boots

- and how can I say

- that they are second-hand?!

- I told

- and you tell her also, that I bought them somewhere, in a good shop.

- B: Now I am writing her to pay attention to the reaction

- She has not answered yet

- C: ((laughs))

- B: She doesn't answer and I ask:

- Are you from Saghoria?

- K answers: yes (.)

- A. She wrote : Yes

- What about you? ((laughs)) (-)

- I said ((laughs))

- that I will strip your hair

- I will drag you, I said ((laughs))

- C: Wow, I feel bad ((laughs))

- I will show you the amusement

- A: Yes, do you know what did she do? ((laughs))

- B: [Whose sweetheart are you taking away?

- C: Mummy ((laughs))

- Wow, I do not take away (-) ((with a little girl's voice))

- M. It does not characterize me ((with a little girl's voice))

- ((everybody laughs))

- B: You, a wanton

- M [I said

- A: And at the same time writes to me, girl, who is she? ((laughs))

- She was shocked

- M I am consoling. There is a misunderstanding and everything will be clarified ((laughs))

- C: Mummyyyy

- "Stand me upppp" ((laughs))

- Wow, we crept on the floor

- A: It was great

- Wow, Chumburidze... now...

- M I am not guilty (-), he came himself ((fictional citation))

- ((everybody laughs))

B and A told a funny story to C. B began the conversation. Firstly, she tried to find out if C knew how Chumburidze had been deceived (lines 1-2). After receiving a negative answer, she began telling a story and used lexical repetition: "I told... I told" (lines: 15/25/27/37). B had contacted her friend from the stranger's website and asked: "where have you bought the boots, which are on you in the "main" photo? (line 9) (a photo presented on the website is implied). Girl's boots were "dzghinki" (second-hand shoes). B and A were informed about that. B asked A to pay attention to the victim's reaction. Chumburidze fell into a trap: she wrote to A, that she could not respond to the speaker from internet, because the boots were second-hand. B asked, if she lived in Saghoria (line 21). The teller's laughter impeded the conversation (lines 22-23). It meant that the funniest was beginning: B began scolding Chumburidze and blaming her, that she was trying to take away her sweetheart. The victim was shocked (line 29). During the process of telling C laughed uninterruptedly. Everybody laughed. It meant, that the story was positively evaluated. The unserious modality of the conversation had cooperative dynamics. A and B helped each other in telling the story. C had a role of a good listener. She laughed and expressed emotions: Mummyyy (line 32); Oh, I feel bad (line 28); "Stand me up" (line 41). She gave A and B a stimulus to go on telling joyfully. The girls also used a citation with a marked voice (lines 33-34) and a citation of a fictional conversation (line 45).

The researches show, that boys' jokes mainly refer to the sexual themes. Vulgar and erotic expressions are often used by them [Bierbach, 1996; Fine, 1987]. Boys aim at entertainment and attainment of the dominant position. A good joker is successful in a group [Branner, 2003: 133]. In the following dialogue the Georgian boy tells a funny story.

Example 2. Boys are speaking:

- A: Shortly

- shortly

- a person from Kutaisi

- two persons from Kutaisi met each other

shortly - and one says, oh, shortly

- I got acquainted with a woman

- I took her to the restaurant

- Invited her to eat (.)

- Then I bought her clothes (.)

- Then I bought golden jewellery (.)

- Then - furs (.)

- B: [end, boy

- A:D [and then, finally

- B finally, I brought her for doing her hair

- Then?

- Then I let her go home

- If you let her go home and did not want to use her

- you could take my wife

- B: Ha, ha, ha ((ironically))

- G: Really? ((ironically))

- A: Really

- B:[Tickle me

- G: [ Have we to laugh finally?

- A: Was it a funny story or=

- B: Drama, drama ((laughs))

- D: What?

- B: The boy has been sitting for 3 hours and telling and didn't you understand?

- D: Start again, start

- A: Two persons from Kutaisi met each other

- B: Ow

- [no, please

- G: we don't want, don't want

- B: Keep silent ((everybody laughs))

- A: Oh, do you know this(--)

- this (-), this(-)

- G: (H) throw out your tongue, we will read

- B: We know, we know

- we have already known

- ((everybody laughs))

- B: I will tell a great one

A was telling a funny story: a man got acquainted with a woman, bought for her everything she needed and finally, let her go home. A's friend said: if you did not want to "use" her, you could take my wife (subtext: I would gain). The funny story was assessed negatively by the listeners. They did not laugh. The phrases: Really? Tickle me, have we to laugh finally? Was it a funny story or a drama? (lines 20-25). Everybody shows ironical attitude towards a teller and a story. It seems, that a negative reaction of young people was not stipulated by the content of the joke. It was caused by the manner of telling, which seemed prolonged and boring. The boys interfered into the process of telling: "Hey, guy, finish" (line 12), "he's been sitting for three hours and telling" (line 21). The teller tried to speak about something else, but he could not manage to do this: "Oh, do you know this, this" (lines 34-35). The boys did not allow him to tell something and stopped him with the phrases: "Throw out your tongue and we'll read", "We know, we know, we have already known" (lines 36-38). B went on telling the funny stories. The given example is a usual discourse of boys, whose conversation is vulgar. Telling funny stories is some kind of a verbal duel. The winner is a person, who tells better and who knows more cheerful stories. The looser is a person, whose telling does not raise a laugh. A did not manage to tell something interesting and jolly. For that reason, he was stopped.

After unserious and joking modality, the modality of irritability and teasing prevails in youngsters. Teasing takes place mostly between the young people of opposite sex - the so-called heterosexual teasing. For example: "George loves Ann". At an early age teasing occupies one fourth of the interaction, for the middle aged adolescents it reaches 50% [Krappmann, 1995: 195]. Jesting, mockery and ridiculing are inseparable parts of young people's everyday life. This type of modality is more frequent among boys, because jesting and mocking are indicators of masculinity and maturity. Teasing has the modality of playing and joking, while jesting is an emotional activity, which stands between provocation and joking or irritation and plying [Günther, 1996: 102]. During jesting speakers are criticized and laughed at. Interaction is mainly accompanied with the laughter. The development of the modality of jesting during the interaction greatly depends on the victim. He/She encourages it or stops the conversation. If a victim has an aggressive reaction, jesting turns into a serious quarrel.

At an early age, teenagers frequently interact via: ironical remarks, mocking at the victim's appearance, playing with words via using the victim's name or surname, imitation. Sarcastic remarks and funny questions are comparatively rare, but their usage is intensified in the period of adolescence. The victim is mocked for his/her bad appearance (39%), excessive weight (13%), limited intellectual and physical abilities (15%), family status, unhygienity or national origin (10%). Mocking at somebody's appearance is more frequent during girls' conversations (girls - 48%, boys - 29%). Boys mainly laugh at others for being unsportsmanlike, having friends among girls and having fear of something. They mock at the members of other groups, although this type of modality is acceptable in their own groups.

Example 3. Boys are speaking:

- A: I broke a branch and tore the leg

- B: "I have died for you" ((with a woman's voice))

- G: Mummy, why am I alive ((with a woman's voice))

- D: [I am so sorry

- B: I had a little heart and it has burnt

- D: Oh, I am so sorry

- Oh, my heart ((with a woman's voice))

- B: I won't sleep tonight

- A: Ah, I'll pull out your hoofs.

- B: I'll pull out your hoofs and ha, ha

- Wow, mine bla

- G: take away your hoofs

- A: Have you visited a cobbler?

- Q (h) Your head seems like dashed at a pestle

- B: Taste is not argued (.)

- G: It's argued. That's why, we are arguing

- A: Long hair suited you more

- (h) Your figure is good, height - also,

- if you had that hair

- I would pass my hands ((everybody laughs))

- B: Yes, brag in the people. O.K.

- M. When we will be alone ... (--)

- A: I don't like you any more <> ((everybody laughs))

- (h) you ought to cut bob

- G: not bob

- Podium ((laughs))

A hurt his leg and whimpered. Other boys jest at him. They use marked voice (a woman's voice) and expressions specific for a woman: "I have died for you"; "Why am I alive"; "So sorry"; "I had a little heart and it has burnt"; "Oh, my heart" (lines 1-8). It means, that A is compared with a woman. It is insulting for the Georgian boy (not in case of unserious modality). A tries to follow the modality of the conversation. Hence, he seems irritated and addresses boys with a threat having typical unserious modality: "Ah, I'll pull out your hoofs". This expression means, that a boy threatens to beat others (lines 9). A does not stop and tries to answer the attacker in order to win this verbal duel. He speaks about the hair-do of B and compares his figure with a girl's one. If B did not cut the hair, he would be regarded as a girl (lines 18-20). B does not like A's words and threatens, that they will speak alone (lines 21-22). A goes on joking and makes B laugh using the following sentences: "I don't like you any more"; "You ought to cut bob" (lines 23-24).

The given example proves, that jesting and mocking have different socio-linguistic functions. On the one hand, it is a possibility of expressing the opposite idea and negative attitude. On the other hand, it can weaken tension in the group of youngsters and deepen their friendship. If a speaker wants appropriate perception of his unserious talk, the information must be given quickly with the change of intonation, defiant key, increased tempo of speech, laughter, smile and appropriate elements (lines 23-24). A person's respond greatly depends on the following factors: the situation, a partner's character and lingual actions, a speaker's and a partner's relationship, a context of a discourse and an onlooker's reaction. If the victim reacts with a joke, it means that he treated a verbal attack as a joke, for instance, B's laughter implies the maintenance of unserious modality throughout the conversation.

Swearing in groups does not have a serious modality. It is used for entertainment and playing. In scientific literature unserious cursing and swearing is called "ritual swearing" [Schmidt, 2004: 200]. It's a kind of a verbal duel. Ritual swearing can become serious. The conflicts created through playing are needed for boys to show the language abilities and to win a verbal duel. During ritual swearing, boys use scabrous, obscene swearing. Playing with swear-words is also met in groups of girls. They use a bad language for imitating boys. During "ritual swearing" girls mainly damn and menace.

In Georgia, a traditional form of a verbal duel is an improvised verse. The verbal fight is carried out with vulgar rhymed poems. Almost every Georgian boy knows a rhymed verse full of rude words and correspondingly, can perform a ritual of citing improvised verses.

Example 4. The boys speak:

- B: Ah

- My lovely motherland when will you blossom

- A: When will you blossom, you?

- B: Do you love anybody?

- I am sowing my grain in the arable land,

I want a pure harvest

Everyone can compete with me in the love of Kutaisi - A: My life is debts,

- wine, duduk, women he, he, he

- B: Something, that makes you active, factually, harms you

- A: The ringing began,

I thrashed you roughly and the USSR was created - B: Here is a board, there is a board

I beat you so, that I could not recognize you - A: Taxis are rushing,

The counter is writing

Doughnuts are so good - B: I don't care about a doughnut. I want a father's sister (-) or a woman.

B said a phrase from the verse, which is followed by A's ironical remark: "When will you blossom?" B did not like this ironical deviation, because he had told the verse with a patriotic inspiration. He aggressively asked A: "Do you love anybody?" and said a poem about the love for Kutaisi. Later A replied with the so-called shairi. B did not delay the answer. The boys had spectators. They did not interfere into the conversation. They laughed and supported the verbal debate (we consciously evade the presentation of the whole version of the conversation). The boys' duel developed into a scabrous improvised verse full of non-normative vocabulary. During similar debates abusive words and sentences are not considered as offences. Moreover, the abuse of the members of family is also acceptable. It's important, because, generally, the Georgian boys do not forgive their mother's or sister's insult.

All he above mentioned does not mean, that teenagers do not speak seriously. Like many adults, they talk about problems, key issues, make analysis and conclusions. Talks of a serious modality may be accompanied with the aggressive modality or the modality of cooperativeness. An aggressive type of speaking is more typical to boys. In their peer groups conflicting situations are more frequent, than in the girls' groups. Boys express their aggression with many vulgar words.

Example 5.

- B: Hey, boy, come here, I will tell you, I will tell you,

- shortly, you are a tube

- Z: What↑

- B: <((acc))> I will explain

- <((acc))> I will explain

- why are you a tube

- Z: I am not a tube and I have never done something like it and never=

- B: = Just a minute↑

- I am standing with girls and you are kicking me, boy.

- It's "tubing". You must not do that.

- Z: =you have done worse "tubing"

- B: [What?

- Z: Fu, your ((beats B))

- S: Go away

- A: [part them, guy

- ..[[..

- B: You, debauchee =

- Z: you tube, you tube, you=

- B: [Let him go

- E: [hit him, boy

- B: Let me go

((A and D are parting)) - (1.)

((Do not beat each other)) - A B: I was unfairly hit

- K: You are cretin. Girls were standing

- Z: Will I swear? Will I swear ↑

- Your father is a tube, your father

- B: Girls were standing there

- Were standing and he came and kicked

- You were there, weren't you? Tell then ((addresses E))

- E: Why do you require my answer?!

- B: Say, boy↑

- Z: Hold your head, boy

- hold, boy

((D laughs)) - B: Don't laugh, boy ((goes away))

- Z: Don't go, boy

- Let's stand aside

- B: (? ?)

- Z: Why do you go and speak?

- B: (? ?)

- Z: Don't speak behind my back or (H) your ass will burn (--)

- B: ((returns)) What do you want?

- Z: [Let's stand aside

- B: [ you have to understand others (.)

- Girls were↓

- Z: Let's go

- B: Go away and I will come. I am not afraid, boy

((goes)) (-) - °°bla°° What will you do? Will you kill me or will you do something else?

The boys are quarelling, because Z abused B in the girls' company (line 9). B tries to explain Z why he behaved like a tube. Z does not endure the name tube and the conversation turns into hand-to-hand querral (lines 13-21). During quarrelling the boys swear, use abusive words, interrupt each other (the conversation was interruted 9 times), try to express their opinion and do not listen to each other. They use imperative sentences (for example: Let's go! Let's go! Come, boy! Just a minute, boy!), young people's jargon (for example: tube, "tubing"), slang forms of address (boy, you tube, you debauchee), Russisms (karoche (shortly), spravedlivi (unfair)), collocations (hold the head, hit somebody). The dynamics of the conversation is competitive, while the modality is serious and aggressive. Girls are also falimiar with a direct aggressive conversation. Hence, it is more frequent in boys.

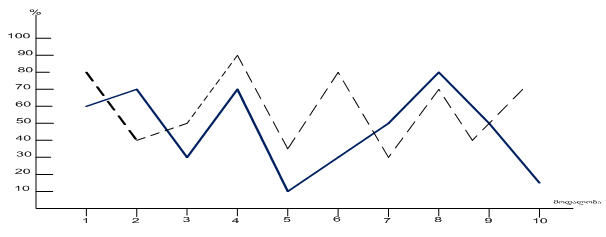

All the above mentioned examples reveal, that the choice of the modality of teenagers' interaction is very wide. During the conversation the modality is changed very frequently. For example, a serious modality may become unserious and vice versa, an unserious modality may be interrupted by a short serious parenthesi, etc. On the basis of the empirical material, the percentage rate of the modality of young people's discourse can be presented in the following way (see the scheme: Girls' and boys' interactive modality): in boys: joking 80%, serious conflict 50%, ritual swearing 90%, improvised verses 40%, berating 80%, aggression 70% are more frequent; in girls teasing 70%, irony 50% and serious talks 60% are more frequent. Percentage rate of joking among girls and boys is similar (boys -70%, girls - 80%). Therefore, an unserious modality is more characteristic for the adolescents (mainly: joking, jesting, teasing, irony, ritual swearing) than a serious one.

Scheme: Girls' and boys' interactive modality

![]() girls

girls

![]() boys.

boys.

- Jesting (boys 80%, girls 60%)

- Teasing (boys 40%, girls 70%)

- Serious conflict (boys 50%, girls 30%)

- Ritual swearing (boys 90%, girls 70%)

- Dissens/Improvised verse (boys 40%, girls 10%)

- Berating (boys 80%, girls 30%)

- Irony (boys 30%, girls 50%)

- Joking (boys 70%, girls 80%)

- Serious conversation (boys 40%, girls 60%)

- Aggression (boys 70%, girls 20%)

[1] [1] (-) kurze Pause; (- -) längere Pause (weniger als eine halbe Sekunde); (1.0) Pausen von einer Sekunde und länger; (? ?) unverständliche Stelle; ..[.... der Text in den untereinanderstehenden Klammern überlappt sich; ..[[... Mehrfachüberlappung verschiedener Sprecher/innen; = ununterbrochenes Sprechen; (h) integrierter Lachlaut; ? steigende Intonation; . fallende Intonation; °°bla°° sehr leise; Tonsprung nach oben; ¯ Tonsprung nach unten ((liest)) Kommentar zum Nonverbalen; <((acc))> accelerando, zunehmend schneller. [Selting, 1998: 91]

References

| Bierbach, Ch. 1996 |

Chi non gaga un kilo – zählt 20 Mark Strafe! Witze von Kindern zwischen zwei Kulturen . In Kotthoff, Helga (Hg) : das Gelächter der Geschlechter. Humor und Macht in Gesprächen von Männern und Freuen. Konstanz : Universitäts- Verlag Konstanz. |

| Branner, R. 2003 |

Scherzkommunikation unter Mädchen. Angevandte Sprachwissenschaft. Herausgegeben von Rudlof Hoberg. Band 13. Peter Lang, europeischer Verlag der Wissenschaft. |

| Deppermann, A. 2001 |

Authentizitätsrhetorik: Sprachliche Verfahren und Funktionen der Unterscheidung von „echten“ und „ unechten“ Mitgliedern sozialer Kategorien. In : Essbach, Wolfgang (Hg): wie/ihr/sie. Identität und Alterität in Theorie und Methode. Würzburg: Ergon. |

| Duden. 2003 |

Deutsches Universalwörterbuch. Dudenverlag, Mannheim-Leipzig-Wien-Zürich. |

| Fine, Gary A. 1987 |

With the Boys. Little League Basaball and Preadolescent Culture. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. |

| Günther, S. 1996 |

Zwischen Scherz und Schmerz _ Frotzelaktivitäten in Alltagsinteraktionen. Scherkommunikation. Hg. Helga Kotthoff. Opladen: Wesdeutscher Verlag. |

| Kallmeyer, W. 1988 |

Konversationsanalytische Beschreibung. Soziolinguistik. Hg. Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar u. Klaus J. Mattheier. Vol. 2 Berlin, new York. |

| Krappmann,L. Oswald, H. 1995 |

Alltag der Schulkinder. Weinheim und München: Juvente. |

| Neumann-Braun, K. Doppermann, A. 1998 |

Ethnografie der Kommunikationskulturen Jugendlicher. Zeitschrift für Soziologie. 27.4. |

| Schmidt, A. 2004 |

Doing peer-group. Die interaktive Konstitution jugendlichen Gruppenpraxis. Frankfurt: Peter Lang (Europäische Hochschulschriften). |

| Selting, M. 1998 |

Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem. In: Linguistische Berichte 173. |